Road Rash: EA’s Riskiest Game Ever Made

Time to be honest. When I was a kid, I saw advertisements for Road Rash all over GamePro magazine when the game launched in 1991. But I never played the game until a few days ago…33 years after its launch. It was a game that I was always familiar with, but other games had always beat it out at the rental counter (see kids…back in the day, we used to be able to rent games from a store…) So it wasn’t until my friend Dan told me he was a fan of these write ups and requested one on his favorite game growing up, which as you may have guessed, was Road Rash for the Sega Genesis. Dan, this one is for you, man.

The EA Is Coming from Inside Your House!

Early EA Didn’t Make Games

In 1990, Electronic Arts (EA), wasn’t the juggernaut it is now. They were a game publisher, but didn’t develop their own games in-house. Instead, they relied on other game developers to create the games and then EA distributed and marketed them. The primary focus of EA was publishing games for DOS, Apple II, Macintosh and Commodore 64. The company steered clear of home consoles because EA’s founder, Trip Hawkins, was still in fear of the video game bust that happened in 1983 (for those who don’t know, video games exploded in the late 70’s and early 80’s, but then fell out of favor quickly in 1983, causing a massive crash in the industry, with Atari bearing a large brunt of it.) The home computer market seemed like a safer bet in his eyes, so throughout the 1980’s the company stuck with the tried-and-true formula of publishing other studios’ games to the personal computer market.

“At the time, the memory of the Atari crash was still very present, so most of the company’s focus was on PC Games,”1 said Road Rash Producer and Designer, Randy Breen.

But the tide was turning in the home console market. The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) had been a huge success, and Sega was also having success with their Master System and had just launched their 16-bit Sega Genesis in the US. The tumultuous home console market was not just heating up, it was on fire, and EA decided it was time to enter the home console market.

Home Console Market & Internal Development

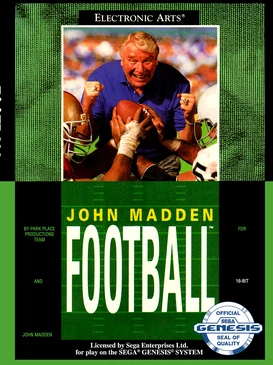

In 1990, EA decided to bring over its Apple II hit, John Madden Football, to the Sega Genesis. The game, originally created by Bethesda Softworks (yes, that Bethesda), was a hit on the Apple II, and EA worked with Park Place Productions to create the Genesis version. EA’s Randy Breen worked through many development and legal hurdles to get the game released on the Genesis. EA composer Don Hubbard provided music for the game and EA artist, Arthur Koch, provided many of the tackle animations.

As part of the move of going into the console market, EA also made another big move. They would begin developing their own games, not just publishing games from other developers.

After completing John Madden Football, EA tasked Breen with making a driving simulator called Mario Andretti Racing. The game would be created entirely in-house by EA. Lead programmer, Dan Geisler, was also brought onboard the project. Geisler had previously worked at Spectrum HoloByte and had worked on the open world driving game, Vette!

Breen had previously worked on Indianapolis 500 for Amiga and DOS, and while he was happy with how realistic that game had turned out, he was was not happy with the lack of fun it brought. “It was a straight sim, probably the most boring kind of racing you can get,”1 Breen would later say.

But EA had already secured the licensing rights to Andretti’s name and the game would need to be a driving simulation similar to Indianapolis 500.

Roads? Where We’re Going…er…We Actually Need Roads

The plan was to make Mario Andretti Racing game for the NES, which was still wildly popular. It was a safe bet for EA. Make a racing game with a big name on a popular console. If EA was going to dip their toes back into the console market, this was a good bet.

The first task in making the racing game was to create the road effect for the driving game. And this is where EA’s plans started to go off course.

Creating a road effect required scaling sprites within the game to increase in size to make them look like they were getting closer to the player. Other NES games, such as Rad Racer, had already used this effect. However, one of the requirements for the Mario Andretti game was to make banked turns, not just have flat roads that go over hills once in a while. Tasked with creating the road effect was Carl Mey, the technical director for the game.

Mey quickly found out that the NES simply couldn’t handle the banked turns needed for the game.1 The only console that could realistically handle it was the new Sega Genesis, which had just landed on US shores a few months prior.

Now EA had a decision to make. Would they jump over to a brand new console that was still trying to get off the ground in the US? The sure bet was now looking riskier. But EA knew they had a team of all-stars working on the game, so they decided to roll the dice and go with the new console.

Moving Away from Cars

So, development of Mario Andretti Racing went to the Genesis. At least EA still had a big name associated with the game with Andretti, and racing games didn’t seem to be too big of a risk.

However, Breen, Mey, and Geisler got together with fellow developer Walt Stein, and started brainstorming a different type of racing game that wouldn’t follow the same boring simulation formula. They hated that driving sims wouldn’t allow you to continue if you crashed, and that the courses were monotonous and boring to drive over and over again. They wanted to do something different.

Mey and Geisler pitched using four-wheelers as the vehicles instead of cars.2 Four-wheelers would work on the tracks they were prototyping and would be something very different from standard race cars. Breen, on the other hand, pitched his own idea.

“I felt there was an opportunity to make driving games more fun and reach a wider audience,” Breen said. “I was big into motorcycles and thought they could add more entertainment value with characters you could see rather than with cars only visible from the rear or a view from inside the cockpit…”1

Geisler also rode motorcycles, and remembered a trip he took to L.A. “I’d driven on Mulholland Drive and thought, ‘Man, if you wiped out here, you’d get some serious road rash.”2 He pitched a name for the new motorcycle game.

Road Rash On Mullholland Drive

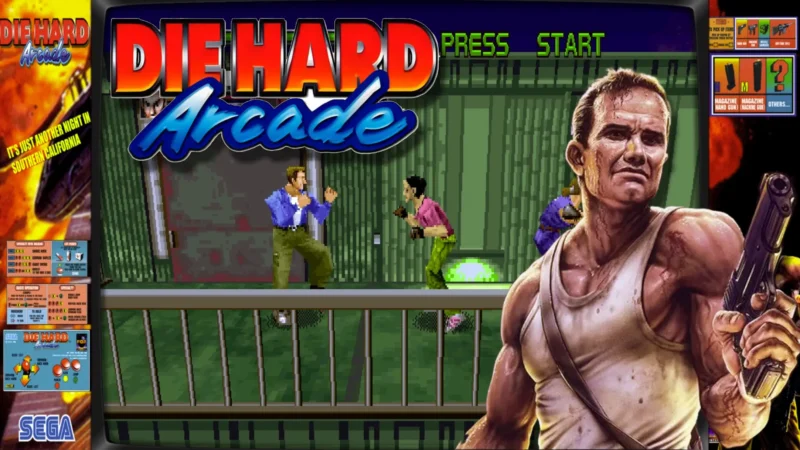

The name the team used to pitch a completely different game than the one they were tasked with making was Road Rash On Mullholland Drive.2 The executives at EA were skeptical. Motorcycles weren’t popular in video games. Sega had success with their arcade racer, Hang-On, but that was back in 1985, five years prior. The other popular motorcycle game was ExciteBike, but that was even older and was a 2D scroller. Motorcycles were a risk.

And moving to motorcycles meant losing the Andretti name on the game. The Road Rash On Mullholland Drive team was asking EA to:

- Develop a game on a brand new console that could fail like the Atari

- Not use the name of one of the most popular drivers in racing

- Make a game with motorcycles, when just about every other racing game had cars

Every “safe bet” that EA had for the game was now out the window.

But the Road Rash On Mullholland Drive team persisted. They brought up another benefit of using motorcycles. Despite the Genesis being much more powerful than the NES, it still had limitations in terms of how many sprites (or individual objects) on the screen at once before the game would flicker. Cars took up more real estate and sprites than something smaller like motorcycles. Using motorcycles meant there could be more action on the screen.

Not Just Racing…

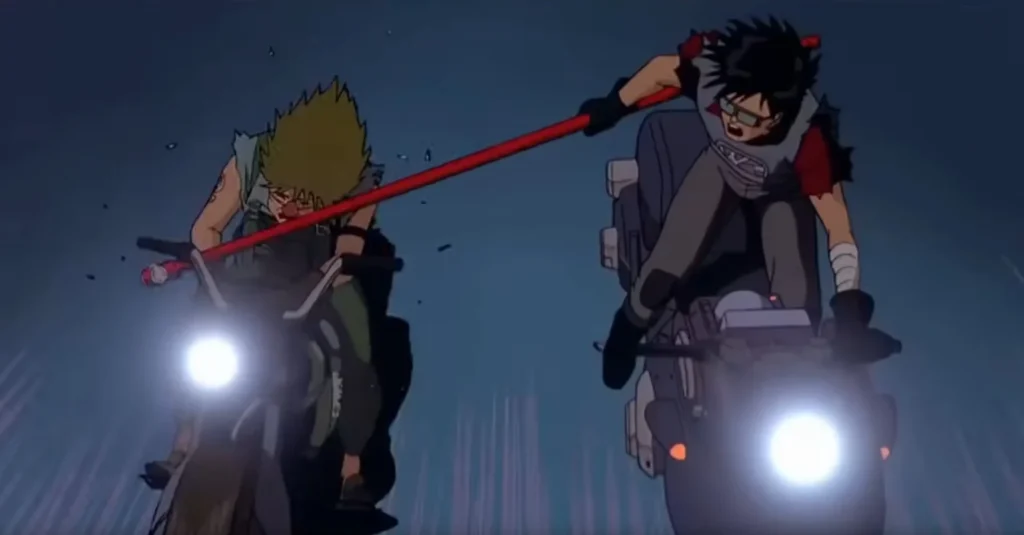

The final benefit of using motorcycles was to bring in the real differentiator of the game. Breen enjoyed watching the kicking and punching that would happen in MotoGP races as well as the biker gang fight scene from the Japanese classic, Akira.

That differentiator was combat. Not only would you have to race other bikers, but you would need to battle them. The player would be able to kick and punch at other racers, while those other racers would gradually start wielding weapons, which the player could also take from them and use.

The idea of adding combat to a racing game was still a bit novel, despite previous racing titles like Spy Hunter and R.C. Pro-Am utilizing the ability to attack your opponents. Road Rash On Mullholland Drive would be different because it featured a behind-the-racer view instead of an overhead view or isometric view like previous combat racing games. This was also about two years before Nintendo would come out with the original Mario Kart for the SNES. What this small team at EA was doing was a bit revolutionary, and a big risk.

Executives at EA had a decision to make. Would they walk away from the safe bet and put their limited resources and internal game development reputation on a wild idea that didn’t fit any single genre?

Breen and the rest of the team must have made a solid argument, because ultimately, EA greenlit the project.

But the name was too cumbersome. It had to be shortened to just Road Rash.

Early Build of Road Rash

The team got to work on the game with Dan Geisler working mostly on getting the driving visuals and road effect to look correct. Other racing games like Pole Position had used sprite scaling to make it look like objects were getting closer to you as you drove, but Geisler and the team were looking for something even more realistic. They poured hundreds, if not thousands of hours into the project, trying to make the driving look as realistic and smooth as possible.

It took them 6 months to get it right.

“When I finally got that road effect down, people saw it and got ill, so I thought, ‘Ah. That’s it. It works,'”2 Geisler would later say. The realism of going over hills, tearing around turns at breakneck speeds was there. He toned back some of the speed to keep players from getting sick, but the foundation of a racer was now in place.

(front row): Michael Bartlow, Peggy Brennan, Connie Braat, Randy Breen, Walter Stein, Jeff Fennel, Dan Geisler. (back row): Paul Vernon, Cynthia Hamilton, Michael Lubugin, Arthur Koch.

The team started adding in the details, including computer-controlled bikers that would attack the player and normal cars that made up normal highway traffic. Already a year into development, EA was starting to worry about their risky bet with the game and asked the team for a demo.

A Demonstration of Demolition

Road Rash needed to be demoed to management at EA, and the team knew they were in trouble. Despite having a lot of good things in the game, they weren’t even close to ready.

Breen recalled, “Our first demo didn’t go well. EA was showcasing Genesis products and demonstrating them well before launch. We struggled to maintain a reasonable frame rate and the animations weren’t effective.”

Using motorcycles over cars, was supposed to result in a game being fast and action-packed. That was the promise made to EA executives during the initial pitch. But Road Rash was anything but. It was slow, choppy, and dull. EA also wanted a demo to show at the upcoming 1990 Consumer Electronics Expo (CES). That demo was also choppy and didn’t show well.

Road Rash looked like it was going to crash and burn.

Road Rash on the Chopping Block

The poor demos set Road Rash back, and soon Breen found himself in meetings with EA management about the future of the project. Road Rash had been a risk to make from day one, but now, a year into development, the game was looking like a bad bet.

While Breen tried to save the game from EA’s top brass, the team added unofficial lead artist Arthur Koch, who had previously worked on Madden. Koch needed to started getting involved in all visual aspects of the game and get it right, quickly.

Koch had to work with the limited palette of the Genesis, which could only display 61 of the 512 available colors at once on the screen (on paper it’s 64 colors, but three of those colors are for transparencies).4 The two other artists on the game, Connie Braat and Matt Sarconi worked with Koch to better understand the in-house tools EA used to create realistic art that fit the confines of only using 61 colors at a time. The art team worked tirelessly to create more realistic objects and went into painstaking detail on the bikes themselves, incorporating a full heads up display and dual rearview mirrors for players to see who was coming up on them. Players now had a 360 degree view of their race, adding to the intensity and fun of the game.

Dan Geisler continued creating new maps and courses for riders, all based on real areas of California. Geisler was able to optimize the roads so well that he “could have mapped out all of the California coast” and fit it all in the Genesis’ memory. He and the team ended up creating 5 courses in incredible detail – Sierra Nevada, Pacific Coast, Redwood Forest, Palm Desert, and Grass Valley. As players got through the game, they would progress to harder and harder and longer stages of each of the 5 courses.

Geisler and Walt Stein worked on optimizing the game’s code to run smoother so it could seamlessly display everything on screen without frames slowing down or having items on the screen glitch in and out of existence.

Breen and team ended up re-pitching the game twice to EA executives, and with the solid advancements it was making, EA stuck with the risky project. But the drama was far from over.

More Management Drama

The early builds of Road Rash were not great by any stretch of the imagination, but they did include the motorcycles flying into the air off of large hills. These crazy physics rubbed the management team the wrong way, because a real racing bike could never do anything like that. This time, it was Dan Geisler that convinced the EA management team to give them artistic license to build out the combat and racing physics in a way that worked for the game.

Arthur Koch remembered, “Some closed-door meetings happening [with EA’s management]. I didn’t get to hear exactly what they were saying, but they were talking pretty loudly, and they weren’t agreeing.”2

EA also couldn’t (or wouldn’t, depending on who you ask) secure license deals with motorcycle manufacturers, so the team had to rely on fake motorcycle names such as the Shuriken (Suzuki), Panda (Honda), Kamakazi (Kawasaki), etc.

Finally, the EA marketing team was having trouble understanding how to position the game. Was it a racing game that should go up against other racers like The Duel II, or was it a fighting game? Was it a simulation or an arcade racer? The heart of the problem was that Road Rash was creating a brand new genre. To get the messaging right, the development team started working directly with the marketing team, showing them gameplay and walking them through different parts of the game.

Still, the marketing team wasn’t overly enthusiastic about the game because it had already demoed so poorly at one of the biggest gaming conferences, CES in 1990.

Road Rash‘s Final Stretch

The team continued its push to release the game before the end of 1991. The artistic team added crashes that would send the rider flying through the air and required the player to direct the rider back to the motorcycle to get back on and finish the race. These over-the-top crashes were inspired by Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner6 and Koch’s experience making tackle animations for Madden. Adding these animations made even crashing a fun experience.

Carl Mey and Dan Geisler also agreed that using projectiles would not be allowed in the game. Combat would be up close and personal. As much as this sounds like a gameplay mechanic, it was actually due to projectiles being detrimental to the game’s performance and framerate, which they had corrected after the poor demos. All combat would be side-to-side of the rider.

The team also added personalized computer rivals that each had their own personality. This touch gave the game a bit more depth and made the player feel like they were truly making their way up the ladder as they were more and more successful in their races.

A high-octane soundtrack was added by composer Rob Hubbard, who was also fresh off of doing the music for Madden and had previously composed music for Skate or Die.

Finally, the team wanted to make the game multiplayer. Being able to race side-by-side was going to be a great addition, but with everything that had gone wrong during development, the idea of simultaneous 2-player races was scrapped. It would simply take too long and delay the project to a point where EA would surely just cancel the whole thing. Instead, two players could still race, but they each race one after the other. (Spoiler: 2-player split screen races were added in the sequel.)

The artwork was done, the AI was programmed and had personality, the racing was so realistic that it made people want to puke. Now, all that was left was to see if this weird hybrid of a game would actually sell on a relatively new console that had just arrived in the United States.

It was time to see if EA’s riskiest bet would pay off.

Road Rash Releases

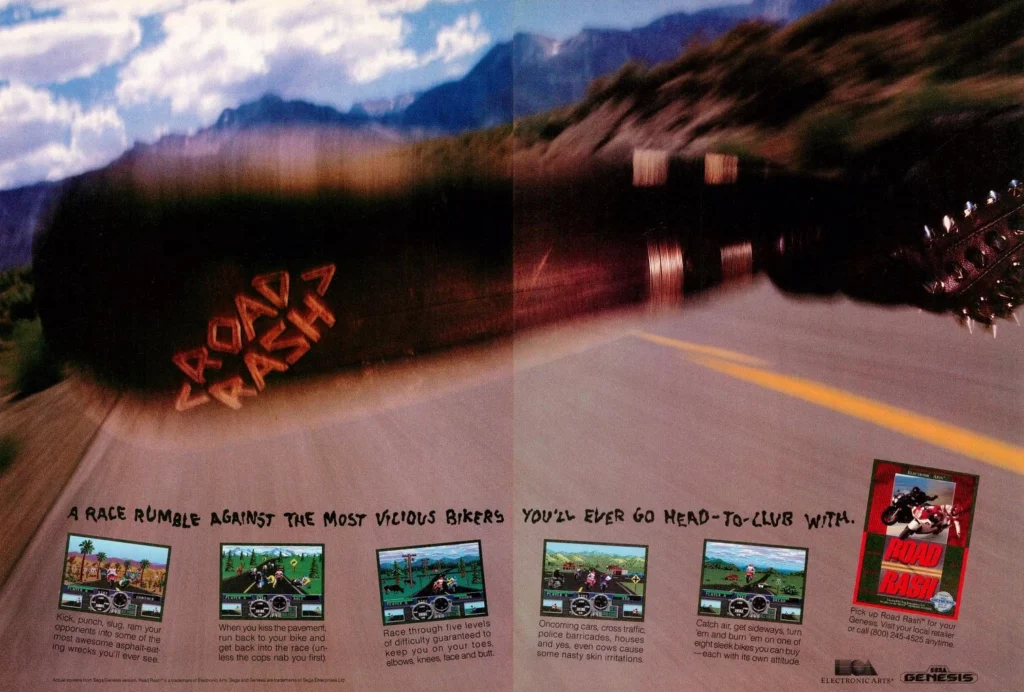

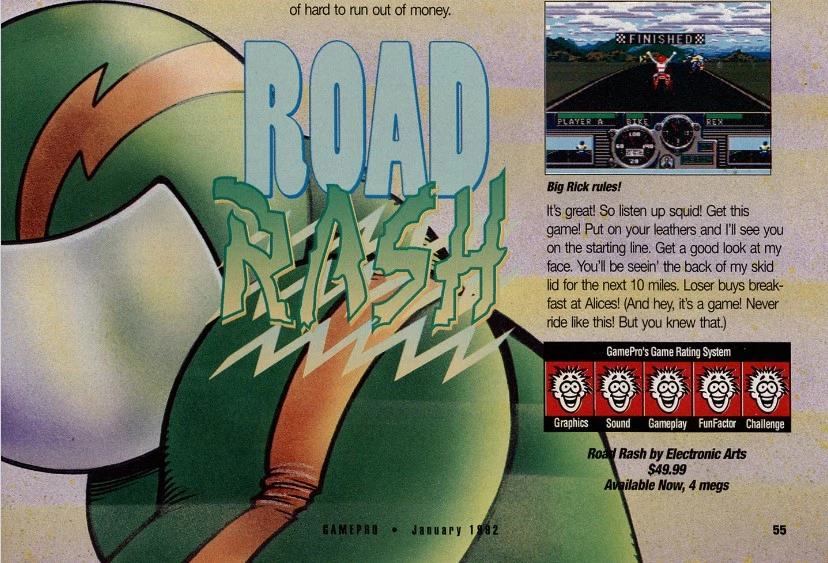

After 21 months of development, Road Rash released in September of 1991. The marketing team at EA put on an ad blitz before the holiday season to pump up the game, taking out multiple page spreads in gaming magazines like GamePro. The game was positioned as tough and gritty, with a focus on the combat.

Breen and the rest of the Road Rash team would have to wait to see how well the game would be received.

The marketing worked. Copies of Road Rash flew off the shelves for the holiday season. In January, 1992, GamePro gave it a perfect score.

Road Rash was a hit.

And not only a hit. It became the most profitable EA title up until that time.

EA’s big bet had paid off. HUGE.

The original version of Road Rash would go on to be ported to several different consoles after the Genesis, including the Amiga, 3DO, Game Boy, Game Boy Color, Sega Master System, and Game Gear. In all, it sold over 1 million copies, not including sequels.

And of course, after that success, there would be sequels. Road Rash II would be greenlit immediately after the holidays in 1991, and would hit store shelves a year later in December 1992. The more refined version of the original included split screen 2-player, maps across the entire USA, and better AI. The original team would return for the sequel with the exception of Carl Mey, who would leave EA for Sega and later help develop Cruis’n USA.

Road Rash‘s Legacy

Not every game has a real legacy other than player nostalgia. But Road Rash‘s legacy as the game that birthed the combat racing genre is just the beginning for this incredibly risky title. It’s success, and the fact that it showed EA that it could create in-house games as good if not better than anything else they’d published from other developers, gave the company a launching point to becoming one of the largest game developers/publishers in the industry.

The company would go on to create a string of console hits throughout the 1990’s including the Madden series, the FIFA series, NBA Live, the NHL series (including NHL ’96, which is my personal favorite), the NCAA Football series, and The Need for Speed.

Had Road Rash failed, or been cancelled entirely, there’s no telling what kind of impact it would have had on EA and their in-house development teams.

Instead, Road Rash raced to victory, despite many bumps and bruises along the way.

References:

- Retro Gamer No. 88, pg. 44-51

- Retro Gamer No. 166, pg. 20-27

- Road Rash (1991 video game), Wikipedia

- List of video game console palettes, Wikipedia

- Interview: Randy Breen, Sega-16

- The 100 Greatest Console Video Games 1988-1998, Brett Weiss, 2022