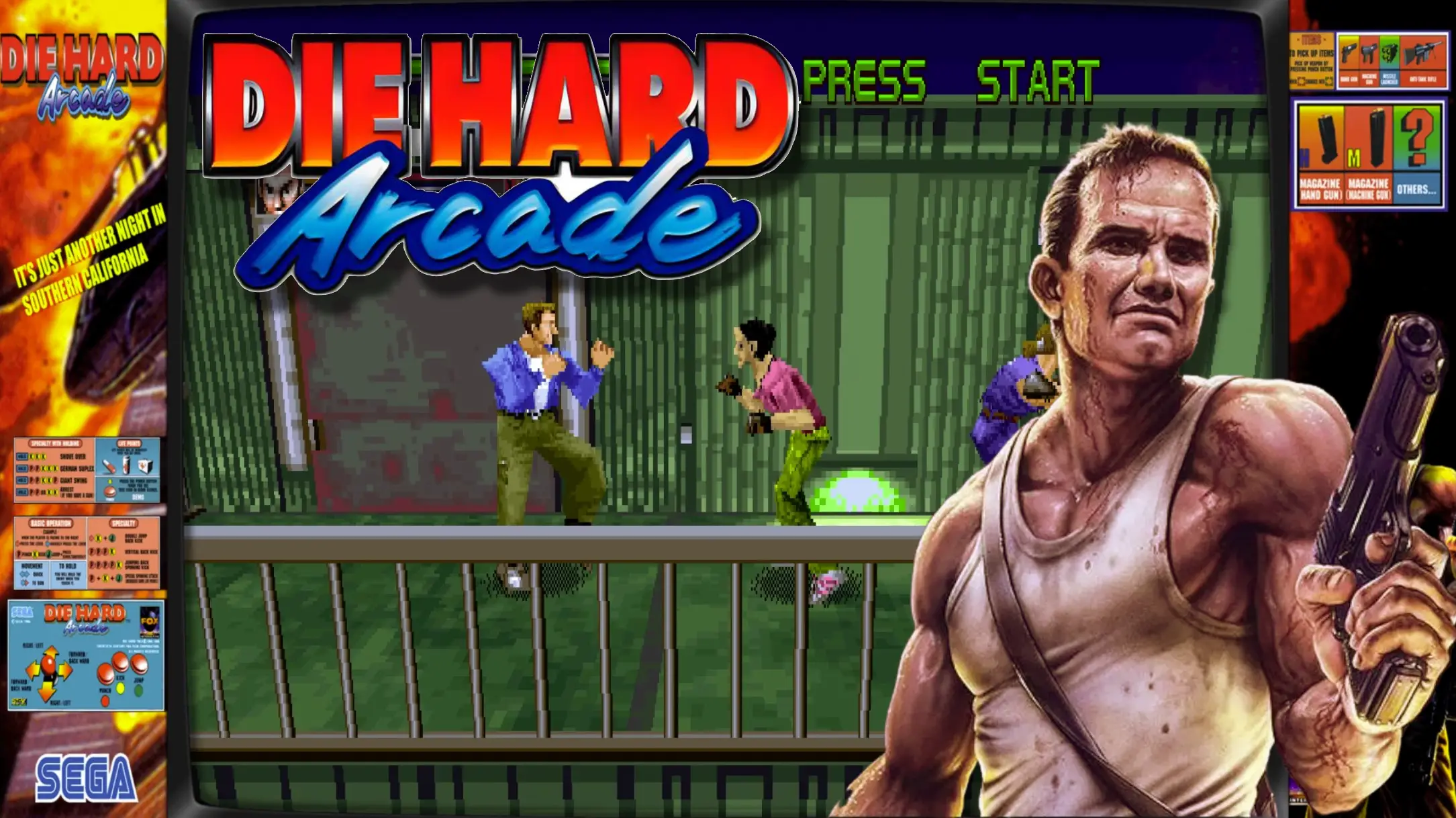

Die Hard Arcade: Sega’s Beat ’em Up Masterpiece

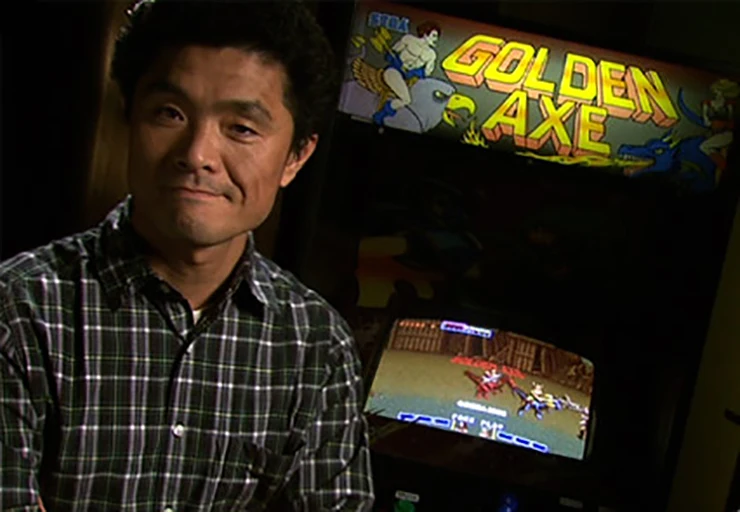

My favorite beat ’em up game of all time is Die Hard Arcade. There isn’t even a close second. Die Hard Arcade came to me on the Sega Saturn, and played it so much I basically had the game memorized. What didn’t occur to me until recently was that my favorite beat ’em up was created by someone who made two other incredibly important games in my childhood, Altered Beast and Golden Axe.

The Games that Made Die Hard Arcade

In 1995, Makoto Uchida had been working for Sega for about eight years, a stretch that started with him being a tester for the game After Burner1. His tenure at Sega was on a steady climb from what very well could have been a shaky beginning.

In 1989, after moving up in the company, he brought up an idea about Greek mythology to Sega’s executives. They liked the idea, but had no team to help him, so he waited six months before he was given a team of developers who were fresh off of making another Sega classic: Shinobi.

The game based on Greek mythology would be a beat ’em up featuring a main character that could power up and transform into mythical creatures, such as a werewolf, weredragon, werebear, and more.

The game was Altered Beast, and Uchida and his team tried to make something revolutionary with its graphics and control scheme. But late in the development, the pressure-sensitive buttons were cut because they were too expensive, and the game launched with lackluster controls.2 Altered Beast launched in arcades in 1988.

A Sophomore Attempt

Altered Beast ended up being a hit when it was bundled with the Sega Genesis for its US launch in 1989, but Uchida and Shinobi team knew they could do better.

In their follow-up game, they decided that the linear action and basic controls of Altered Beast were too simple, so they went about creating a game with the same dramatic visuals, but focused heavily on making a game that controlled well.

In this outing, they went away from Greek mythology and instead went full Conan the Barbarian mixed with Double Dragon. With multiple characters to choose from and two player coop action, Golden Axe launched in arcades in 1989.

Golden Axe was a huge success, and it’s follow-up, Golden Axe: Revenge of Death Adder in 1992 was even better.

Another Dimension…Another Dimension…

Now it was 1995, and Uchida and Shinobi team, which was now just part of Sega AM1 were looking to create their next hit. But the genre they knew so well was getting stale. Sega AM1 programmer, Susumi Hirai would say, “A side-scrolling beat ’em up was not a novel concept at that point. It was an old genre.”

Golden Axe featured a 2.5D isometric playing experience, where the player could move left and right along with up and down the battlefield. However, it was still a 2D sprite game. And these side-scrolling beat ’em ups were getting old by the time the mid 1990’s rolled around.

The development of 3D games was well underway at this point, with textured-mapped 3D-racer Daytona USA coming out in 1994 and taking arcades by storm. The technology was there to create a 3D beat ’em up. However, not all 3D technology was the same.

Sega’s Titan Video System (ST-V) vs. Model 2

Daytona USA was built on Sega’s state-of-the-art Model 2 (M2) board, which Sega co-created with GE Aerospace (later acquired by Lockheed Martin). The board was revolutionizing 3D graphics and powering other Sega classics like Virtua Fighter 2.

But Uchida and AM1 weren’t given the beast of a board. Instead, Sega had overproduced their low-end 3D board, the Sega Titan Video System (ST-V). This board had a fraction of the power of it’s M2 cousin and was designed to run simpler games. In fact, it was ultimately the same board that Sega used in its home console, the Sega Saturn.3

But the directive from Sega was clear to Uchida and AM1: Make a great game for arcades using a console board and processor.

Despite the lack of power, the board was still more powerful than anything used on the Golden Axe games, and with it the team got to work.

Developing Die Hard Arcade

After creating games set in mythical times, Uchida wanted to make a game that felt more like a modern action movie. He wanted the high quality sound of movies and the ability to change camera angles – something he and the team had been unable to do on previous games. The ST-V board had enough muscle to push 3D polygons in a way that would lead to the cinematics Uchida was looking for while providing CD-quality sound.

Next up was the idea of the game. This part came easy to Uchida.

Uchida was a huge fan of action movies, and one of his favorite movies was Die Hard.4 “Die Hard is one of my favorite films. The first time I saw it, I knew I wanted to create a video game based on it. The action and storyline made a big impression on me.”5

However, the game didn’t start with the Die Hard moniker. According to a defunct website, the original working name was Dead Line.8

But before production began on the game, Sega wanted to bring in another team that had worked with Sega’s iconic “Sonic Team” of developers. This team was getting its feet wet in 3D graphics and Sega thought it would be a good idea to have the teams work together. The only problem, the other team was across the Pacific ocean from AM1.

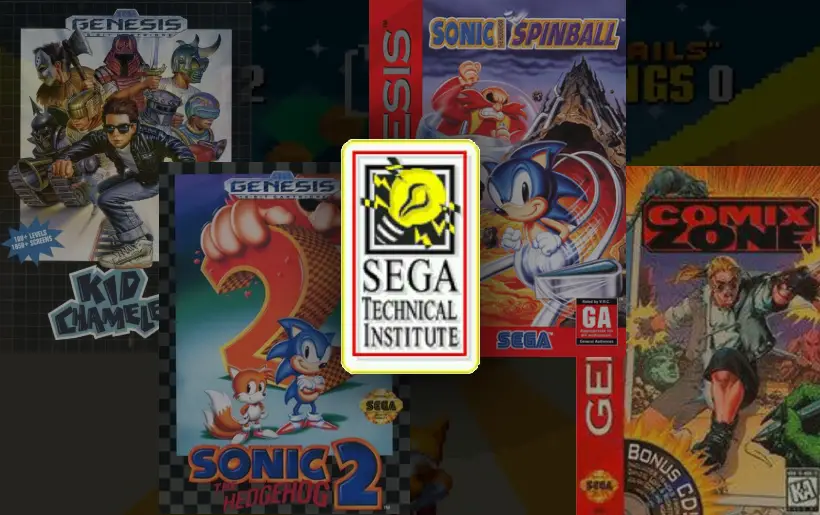

Sega Technical Institute

Sega Technical Institute (which goes by the unfortunate abbreviation “STI”) was based in the US at Sega of America’s office in California. This group was the behind-the-scenes muscle that created some of Sega’s greatest games, including Sonic the Hedgehog 2, Kid Chameleon, Sonic Spinball, and Comix Zone.

STI was split into two groups. One group had what must have felt like the golden ticket. They were in charge of bringing the iconic Sonic the Hedgehog to the Sega Saturn, and had been working on the game for over a year. (Spoiler: That game, Sonic X-treme, ended up being one of the biggest disappointments in Sega history, and is often considered a reason why the Saturn would ultimately fail commercially.)

The other half of STI was working with Silicon Graphics, learning how to create and animate 3D models that could go into Sega’s new Saturn hardware, which was based on the ST-V board. While the team was getting the hang of the graphics, their game designers were having trouble coming up with concepts for their own new games. After all, how were they supposed to compete with their counterparts who had Sonic at their disposal? After a month without a game idea, the highly skilled team of animators simply had nothing to work on.

In a funny twist of fate, instead of Uchida waiting 6 months to get a team to develop his game like he had with Altered Beast, this time around it was the artistic team waiting to get Uchida. STI was just what the programming-centric AM1 team needed: 3D modelers and artists.

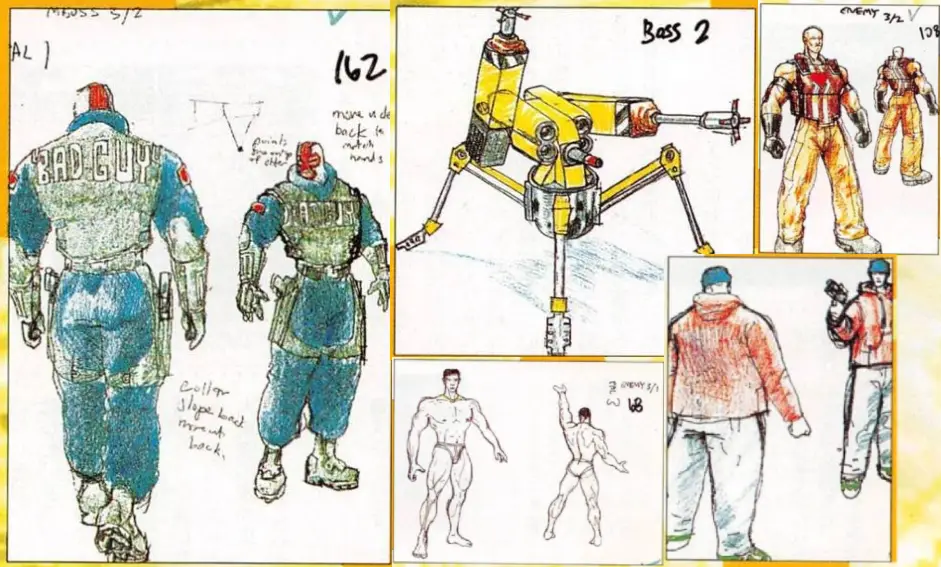

STI and AM1 joined forces in the latter half of 1995, with Uchida and the AM1 team relocating from Japan to STI’s offices in California.4 STI would do the character concept, modeling, animations, and soundtrack while AM1 was in charge of all of the programming.

Despite language and some cultural barriers, the two teams worked well together. STI lead artist and designer Stieg Hedlund would later say, “Any time a piece of art was completed, lead programmer Hiroshi Ando would load it into a test environment for us to see.”

Graphics Hiccups

The beautiful 3D graphics STI created couldn’t be properly handled by the ST-V hardware, and as a result, many models that looked great on an artists PC ended up looking like a blocky mess in the game. The team worked around these issues by developing new processes to get better looking textures on the graphics that the hardware could properly handle.

For many on the team, this was their first time working on a 3D game, so many new processes had to be created on the fly. Due to these limitations, the graphics for the game became very time consuming.

But a game is more than just graphics, and while the STI team polished up what they could with the underpowered ST-V hardware, Uchida and AM1 got to work coding the game.

Making a Playable Action Movie

Most beat ’em ups have two main gameplay features. The first is beating up the bad guys. The second is walking to the next part of the level. From Double Dragon to Streets of Rage and even Uchida’s own Golden Axe, walking from one area of a level to another was a part of most beat ’em ups.

Uchida wanted to change that.

“I thought it would be interesting to show the transition between scenes during the action and to make it as close to an action movie as possible.”5

Instead of walking from scene to scene, the game would feature cut scenes. At first, these were simple pre-rendered cut scenes showing a character going from one part of the building to another. But when the finished scenes were shown to the team, they knew it wasn’t enough. Uchida recalled people saying, “This isn’t really interesting, it’s just a camera floating through a hallway.”5

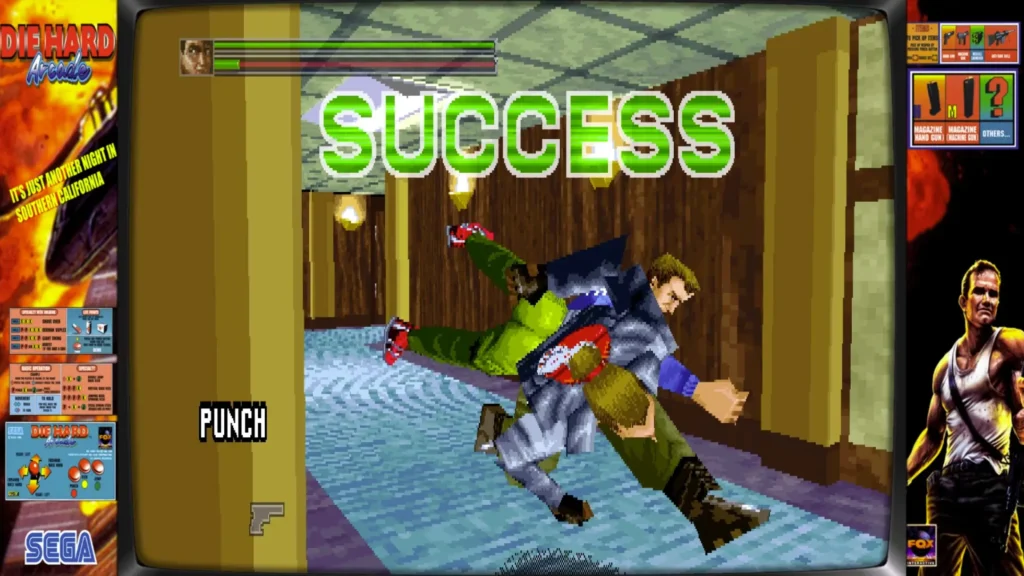

Some members of the team recommended making the cut scenes interactive. These revised cut scenes, known as “quick time events”, now required players to quickly tap the correct button at a specific time during the scene. If the player succeeded, an enemy would be knocked to the floor and the player would continue. But if the player failed, they would be at a disadvantage or have to fight more enemies.

Die Hard Arcade’s Second-to-None Controls

Ever since the gameplay controls of Altered Beast fell well short of Uchida’s vision, he and the Shinobi/AM1 team worked tirelessly to improve the controls for each successive game. Golden Axe and it’s sequel had solid controls that made them stand out from other games in the genre, but Uchida and AM1 decided they were going to throw everything at Die Hard Arcade.

First and foremost, the game would allow for one or two player co-op play just like the Golden Axe games before it. But both characters would have similar move sets.

Aside from the standard attacks of kicking and punching, characters would be able to perform all kinds of other moves too. If you knocked an enemy down, you could jump in the air and land knee or shoulder down on them to inflict more damage. You could grab opponents and and knee or punch them before doing a finishing move such as a suplex or a giant swing.

In all, the team would add over 50 different moves a player could do, including simply arresting bad guys if you had a pistol in your hand. Speaking of pistols, Die Hard Arcade would go far beyond any other game at the time in terms of weaponry.

Die Hard Arcade Weapons

Special emphasis was put on making the weapons in Die Hard Arcade as amazing as possible.

“Having lots of items like in the previous game [Golden Axe 2], with bigger differences between them and a flashier representation would be really interesting, I felt,” Uchida would say.

Instead of standard beat ’em up weapons like guns, knives, and baseball bats, Die Hard Arcade would feature an insane variety of objects you could use as weapons. Sure, you could fire the gun at people, but when you ran out of bullets, you threw the whole gun at the enemy. In the parking complex you battle firefighters, so of course you have access to axes and machine guns.

But that’s just the start. Sure, adding a machine gun was cool, but what was even better was the missile launcher. But what was even better than that was the anti-tank rifle, that shot enemies clear across the level.

TV’s, oil drums, chairs, grandfather clocks, all could be used as weapons. But the one that stood out the most to many players was the spray can. The spray can was just that, a can that you could spray in the enemy’s face to temporarily blind them. But you could also pick up a lighter at the same time, and just like that you’ve got yourself a flame thrower!

Realistic Character Movements

Developing the game in the United States gave the Japanese AM1 team a crash course in American culture. One thing that stood out to them was how Americans moved differently from Japanese people.

“It seems Americans have more dynamic movements than the Japanese. We found it interesting to observe the movements of people walking down the street in America,”5 Uchida said.

Each character on the screen got their own movements and “personality” that sets them apart from other enemies. Even the two heroes of the game have unique movements and attacks.

“Our group really collaborated to get the movements just right,” Uchida would later say.

Orchestrating the Music and Sound

The sound design for the game was handed over to STI’s Howard Drossin, who had created the sound for Sonic the Hedgehog 3, Sonic & Knuckles, and Comix Zone. Drossin would also work on the ill-fated Sonic X-treme.

Realistic sound effects were added to the game, so every punch, shot, kick and missile to the face was an auditory delight. Enemies would taunt, grunt and scream throughout the game. Special care was taken in adding the spring sound effect followed by a cry of pain when an enemy would get kicked in the crotch.

The sound track would feature thrilling music that fit with the theme of an action movie. Like many beat ’em ups before, the music would escalate as the player got into more danger.

With the sound, characters, movements, and gameplay complete. There was just one final hurdle in getting Die Hard Arcade published.

Getting the Die Hard License

As the game was finishing up development, it was obvious that the game they were creating was an homage to Die Hard, but Sega needed to secure the rights to that name from Fox Interactive.

(When researching this game, there were two accounts of how this happened. One account states that Sega had secured the rights to Die Hard before the game was made7. However, two other accounts4 8 state that Sega secured the rights late into the game’s development. The latter account seems more likely because one is from Uchida himself.)

Uchida explained in an interview, “When the game was 80~90% done, we took it to somebody at 20th Century Fox and said, ‘our game is pretty much just Die Hard, so why don’t we go ahead and make it a Die Hard game?'”8

Sega quickly got the green light to move forward with the license in the US (but not in Japan). However, certain things in the game would need to be changed to keep the license.

First, the main character got a little bit of a makeover to make him look more like John McClane. However, he couldn’t look too much like Bruce Willis, because Sega couldn’t get the rights to use his likeness in the game, hence his strange face that would later appear on the signage for the game.

Second, the building that the game is set in would need to be the Nakatomi building in the US version. An actual model of the building was provided to STI from Fox Interactive to recreate it in the game.

Finally, the game refers to the daughter you’re trying to save as “the president’s daughter” which immediately makes the player think they are rescuing the President of the United States’ daughter. But Fox Interactive told them the game couldn’t stray that far from the movie. “Since the movie didn’t revolve around the president [of the U.S.] , we were told to make the girl appearing in the game into the daughter of the head of Nakatomi,” Uchida would later say. So the game clarifies this in the instruction manual for the Sega Saturn version.

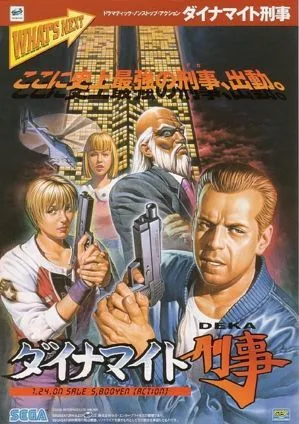

Dynamite Deka in Japan

Without securing the rights to Die Hard in Japan, the game would be released as Dynamite Deka, with “Deka” loosely translating to “detective” in Japanese. The game is basically the same except it doesn’t take place in the Nakatomi building and the characters are renamed. Otherwise the gameplay is nearly identical.

Release of Die Hard Arcade

Die Hard Arcade released globally in July 1996 to positive reviews. The collaboration between Uchida/AM1 with STI created a hit in arcades across Japan and the US. It soon became the best selling American-made Sega arcade game up to that point.6

With its success, Sega was able to clear out their entire backed-up inventory of ST-V boards.6

A year later, Die Hard Arcade would be released for the Sega Saturn. While the reviews for the Saturn port were mixed, with some reviewers complaining it was too short (a playthrough takes about 30 minutes), it was nearly identical to the arcade version because the Saturn used the ST-V architecture that the arcade game was built on.

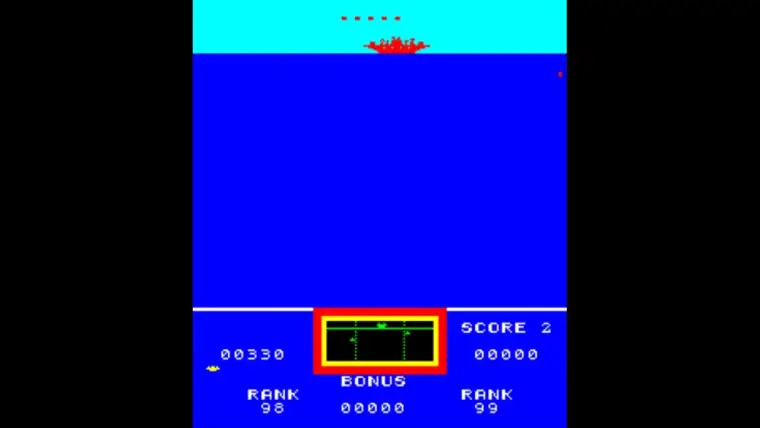

Also included in the Saturn port was Sega’s 1979 arcade game Deep Scan at the beginning. Playing that game would earn the player more credits for their playthrough of Die Hard Arcade.

STI After Die Hard Arcade

Unfortunately, the success of Die Hard Arcade was not enough to buoy the sinking ship that was Sega in the mid-90’s. After the game’s release, the other half of the STI team that was working on Sonic X-treme would have their game cancelled. As a result, the entire STI team would get dissolved, with team members getting redistributed to other areas of Sega or let go from the company.7 Die Hard Arcade would be the last game made by the legendary, but mostly unknown, STI team.

While the STI team did not get the happy send off the team deserved, they went out with a bang and delivered an amazingly fun beat ’em up that to this day is a ton of fun to play.

Uchida and AM1 After Die Hard Arcade

For Uchida and AM1, their vision of creating a modern beat ’em up (a genre that many people saw as being played out) became a reality. It was a nice capstone to many years of refining the genre from Altered Beast to the Golden Axe games and finally with Die Hard Arcade. They would go on to create a sequel to the game, but it wouldn’t include the Die Hard license. Instead, they went with the Japanese naming. Dynamite Cop was released in 1998. While it doesn’t include John McClane, it retains all of the fantastic gameplay of the original.

References:

- Makoto Uchida, SegaRetro

- The Making of Altered Beast: Retro Gamer No. 123

- Sega Titan Video (ST-V) Wikipedia Page

- Horwitz, 2018, The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games, McFarland

- Classic Interview: Makoto Uchida, Sega-16

- Developer’s Den: Sega Technical Institute, Sega-16

- Company Profile: Sega Technical Institute: Retro Gamer No. 36

- Dynamite Cop – 1998 Developer Interview, shmuplations