Daytona USA: Developing an Arcade Classic

Daytona USA is my favorite racing game by a mile, and to this day I still look on eBay for a used Deluxe cabinet that I could someday buy and have in my home. This arcade classic released in 1994 when I was a teenager, and after a port of the game came out on Sega Saturn in 1995, I played so many hours of it that I had perfected each course. As a side benefit, the game helped me learn how to drive in real life, and to this day I still sometimes hum the iconic theme song when I’m on the interstate.

I’m excited for this deep dive, and in doing research for it, I found some unbelievable things had to all happen to make this classic game a reality, including one of the weirdest partnerships in video game history. Here’s the history of Daytona USA.

Sega Gets Lapped

Virtua Racing

Before diving into the development of Daytona USA, it’s important to know the background of how important it was for Sega to get it right.

In 1992, Sega released Virtua Racing, a 3D racing game that was originally just a proof of concept to show off the 3D graphics of Sega’s new Model 1 board. The results impressed the team so much that they decided to blow out the prototype and create a full game from it. At the helm of the game was Yu Suzuki and Toshihiro Nagoshi, two of Sega’s biggest hitters who were in charge of Sega’s internal development team, known as AM2. They developed a life-like racing simulator that had enough arcade action to keep quarters flowing into machines across Japan, Europe and the United States.

But success was short-lived. 3D polygon games and 3D technology grew incredibly fast, and by 1993, one of Sega’s biggest competitors, Namco, handily dethroned Sega as the king of racing.

The Sega vs. Namco Rivalry

Sega and Namco’s rivalry went all the way back to the 80’s when Sega released Turbo, a game that replicated 3D environments by scaling sprites as they passed the car. This revolutionary game was one of the first to feature this “2.5D” technology and give a third-person perspective with true sense of speed and the ability to see what was coming up ahead. Before, this technology, most racers had been top down views that were anything but immersive.

Namco fired back a year later, in 1982, with their own sprite scaling racer. This game would feature a slightly lower 2.5D camera angle, making it even more immersive. The gameplay was also more fluid, with less clipping and draw-in. When Namco’s racer hit arcades, it dominated everything else. Everyone wanted to play the new standard in racing games: Pole Position. Pole Position would go on to rule arcades for years, being the top grossing arcade game in 1983 and 1984. At one point, Pole Position arcades were earning $9.5 million per week in coin drop earnings1.

In 1986, Yu Suzuki would lead up the development of another arcade racing classic, Out Run, which put Sega back on top. But sure enough, Namco would answer in 1987 with Final Lap, which featured up to 8 racers at once. Final Lap would go on to dominate arcades as the top grossing racing game in 1988 and 19892.

Ridge Racer Takes the Lead

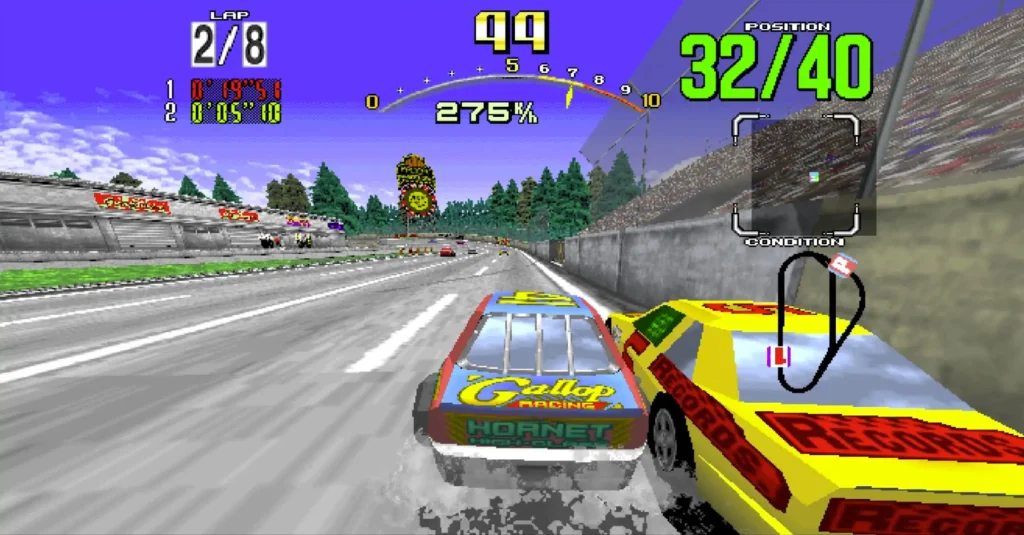

Skipping forward to the early 90’s, Sega was high on the success of Virtua Racer when Namco released Ridge Racer. Everything that Virtua Racer had revolutionized, Ridge Racer seemed to perfect. The graphics blew Virtua Racing out of the water. While Virtua Racing offered relatively smooth gameplay, none of the polygons in it were textured. A red polygon was just red. A gray one was gray. Added together, it made for a game that looked good at the time, but was far from realistic.

Ridge Racer, on the other hand, had texture-mapped polygons, a high framerate – resulting in much smoother gameplay – and the sound was far superior to Sega’s effort. The game was also far more forgiving than Virtua Racing, which played more like a simulator with cars easily spinning out on sharp turns and crashing into walls. Namco’s racer dominated arcade sales in 1993, sending Virtua Racing to the back of the pack.

An Unlikely Partnership

Sega had to come up with an answer to Ridge Racer, and they knew that their Model 1 arcade technology just wasn’t going to cut it. The technology that Namco was now using was potentially years away from what Sega had. Sega was getting left in the dust.

Engineers at Sega hadn’t been able to get the texture-mapping hardware to a place that Namco was already using. However, one of their new partners had shown fascinating technology, that could produce incredible graphics.

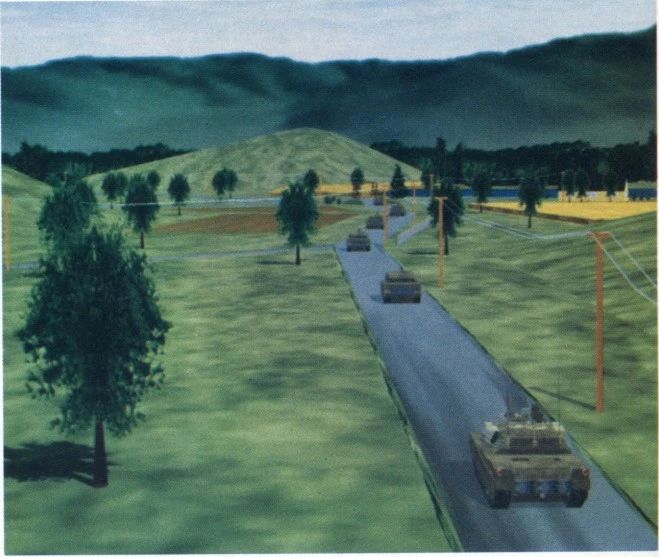

GE Aerospace was in the graphics business because it created military training simulators. With Department of Defense budgets at their backs, they had created some of the most revolutionary hardware and software on the planet for flight, tank, and battlefield simulators. However, they were now strapped for revenue because all of the government funding dried up due to the end of the Cold War. GE Aerospace needed to sell their technology outside of the defense space to keep their operation afloat. Leading up that effort was GE’s Bob Hichborn.

Hichborn and the rest of his team at GE Aerospace would update the simulations after work hours and play them like video games. “I would take my team of interns and we would turn the various training systems into spaceships, race cars, raft rides down river rapids or whatever we could dream up,” Hichborn would later recall4.

Hichborn had pitched GE’s technology to Disney and other theme parks. After a series of “maybes” he called up Sega. Within a month, executives and designers from Sega were at GE Aerospace’s headquarters, which happened to be across the street from the Daytona International Speedway. What they saw blew them away. GE was lightyears ahead of Sega when it came to hardware. GE showed off a a racing simulation, running in real time, that was smoother and better looking than anything Sega had at the time4. Granted, it was running on hardware that cost $32 million7.

GE Aerospace had good news for Sega. The $2 million chip that ran the graphic processing for the simulators could potentially be made for “cheap”. But for GE, “cheap” meant $200,000…per chip. The average arcade unit was selling for about $15,000 at the time.

Yu Suzuki knew Sega needed this technology, but the price tag was simply too high. He would later note, “Nobody at Sega believed me when I said I wanted to purchase this technology for our games.” Suzuki put it all on the line and told Sega executives that he’d be able to convert the $2 million chip into a video game chip that they would to put in every arcade cabinet without breaking the bank.7 Company brass would give him the nod, but the bet, if it didn’t work, could ruin Suzuki’s career.

A deal was struck and GE Aerospace, which was subsequently acquired by Lockheed, would help develop the follow-up to the Model 1 board.

Sega Model 2

GE Aerospace delivered for Sega. The new hardware handled texture mapping (painting polygons with pictures to give them a more realistic appearance), anti-aliasing (smoothing rough edges of pixels), and could push 300,000 polygons per second at 60 frames per second5. It’s estimated that the partnership fast-forwarded Sega’s hardware development by 14 months.4

Suzuki would later say, “I had to take that chip and convert it for video game use, and make the technology available for the consumer at 5,000 yen ($50) per console or else nobody would buy the hardware.”7 But how do you make a $2 million chip for only $50? That’s where Sega’s internal engineers took over.

A huge portion of the cost of the original GE Aerospace chips was in the research and development. The chip itself didn’t have $2 million worth of materials in it. It was simply silicon, metal, and plastic like all other chips at the time. The AM2 team deconstructed the chip to understand how it actually worked. By reverse engineering the chip, the team at Sega was able to get the chip down to a production cost of $50 per chip7.

Suzuki’s gamble had paid off.

With the hardware ready for whatever the AM2 team could throw at it, Sega had a single new directive: Outperform Ridge Racer.

Daytona USA is Born

Taking a cue from GE Aerospace’s location across the street from the Daytona International Speedway, Sega of America’s president, Tom Petit, suggested NASCAR racing over the F1 racing featured in Virtua Racing. Sega’s other company presidents in Japan and Europe were skeptical. NASCAR was only popular in the US. President of Sega Europe, Vic Leslie, voiced the most concern over the move away from F1 racing and going all-in on a game that would primarily target American audiences. However, Yu Suzuki was intrigued at the idea of making a NASCAR game.10

Petit asked for Sega of Japan to do market research and flew out some of the AM2 team to Daytona to see the sport for themselves, which included Yu Suzuki, who was now leading the AM2 team, and Toshihiro Nagoshi, who was tapped as the director of the first game to be featured on the Model 2 board.

Once in Daytona, they attended a race and then get a behind-the-scenes tour of the facility.

Nagoshi would later recall getting to stand on the track itself and feeling the banked turns, “It was so steep that you literally could not stand on it.”6

After witnessing NASCAR in person, and seeing how this simple looking sport was actually incredibly complex and strategic, Nagoshi also threw his weight behind the idea. A NASCAR game was the way to go.

Europe’s Leslie was outvoted because Europe’s share of the arcade revenue for Sega was about a third of that of the US.10

An agreement was made with representatives of the Daytona 500 to utilize the Daytona name, but Sega didn’t pursue the rights to the NASCAR brand because NASCAR wasn’t known globally yet. Instead, they decided to go forward with the project with just Daytona as the hook.

Thus, Daytona USA would become Sega’s response to Namco. Ridge Racer had been in the lead for a while, and now Sega needed to pass it.

With cutting edge hardware and Daytona as the hook, it was now time for AM2 to run with it and create an amazing NASCAR themed game.

There was only one problem.

Most of the AM2 team knew nothing about NASCAR.

AM2’s Crash Course

The Japanese AM2 team knew F1 racing well, it was wildly popular in Japan as well as Europe. But now Sega was directly targeting the US market with Daytona USA and the team needed to do as much research as they could.

Daytona USA was Nagoshi’s first as a game director, and it was up to him to design a game that could knock off Ridge Racer. He surrounded himself in NASCAR culture, reading books about it and watching NASCAR races. He took note of how cars would carefully draft other cars and then snap out and pass them when the opportunity arose. He wanted the AI in the game to behave similarly, causing more difficult levels to include cars that would simply impede the player on purpose and require a well-timed pass to get by.

Makoto Osaki, the game’s planner, claimed to have watched Days of Thunder over 100 times to get a feel for the racing.8

Daytona USA as Funky Entertainment

While getting saturated in the world of NASCAR was becoming Nagoshi’s past time, he also realized that a straight racing simulation would probably not play well in the arcades. It was one of the weaknesses of Virtua Racing. Daytona USA would be able to closely replicate what it was like to drive a stock car in a race with speeds topping out around 200 MPH, but to do that well required being a professional driver with years of training. The arcade unit was going to be played by kids, most of whom didn’t have a driver’s license.

Nagoshi wanted to split the difference. He wanted the game to feel realistic, but still race like an arcade game. He dubbed it “funky entertainment.”8

Unlike real NASCAR, Daytona USA would incorporate a drifting mechanic, which was popular in Japanese street racing at the time. Breaking and jerking the wheel to the left or right would start the car drifting through a tight turn. The player could then maintain the drift and then straighten out once the turn was complete. This mechanic had been used in Ridge Racer as well, which may or may not have caused its inclusion.

Like Ridge Racer, Daytona USA would have three courses to choose from, each progressively harder than the last. The first course would be a similar course to the Daytona International Speedway, but with a tighter final turn and…er…mountains, which are hard to come by in Florida. But the tri-oval track would give new players a chance to get a feel for the game and really race against other cars instead of just racing against the track itself. This aspect of the game was very true to NASCAR, as the courses are not the issue, but rather the other drivers.

And this is where one of the biggest differentiators of Daytona USA comes in to play vs. other racing games. Daytona USA‘s AI would keep track of how well the player would race the first lap and then adjust the difficulty of the following laps. If a player didn’t do well on a lap, the AI would move out of the players way on subsequent laps. If the player did well on the lap, the AI would try to block the player. This dynamic difficulty, or “rubberbanding”, made the game fun for both novice and expert racers.10

Daytona USA would also feature a simple Manual vs. Automatic car selection, just like Ridge Racer. On the surface, the games were shaping up to be very similar. But that Model 2 board would give Daytona USA a major advantage.

Harnessing the Horsepower

With the Model 2 board, the AM2 team had a ton of graphic rendering power at their disposal, but none of them had any experience with the thing that made it so special: texture mapping. Creating simple polygons wasn’t easy, but the team was familiar with it. Now they had to figure out how to map 2D images onto those 3D polygons and make it look realistic. The team resorted to a tried and true tactic for learning: trial and error.

The team’s progress with texture mapping started off slow, but over time the issue went from a weakness to a strength. Soon, every part of the game’s graphics were getting beautiful texture mapping, making Daytona USA truly come to life.

While figuring out the texture mapping, Yu Suzuki reached out to Jeffery Buchanan, one of Sega’s artists/designers, who recommended adding fun things into the backgrounds such as dinosaur fossils into the cliffs. The team ran with the idea and added the dinosaur fossil in the intermediate course, Sonic the Hedgehog into the cliff of the third turn of the beginner course, and Virtua Fighter’s Jeffrey as a statue, the space shuttle and a giant clipper ship in the expert course. These would become iconic set pieces in the game.

The new hardware also enabled the developers to clock the game at 60 frames per second (FPS), on par with Ridge Racer and double the 30 FPS of Virtua Racing. This gave the entire game a smooth and realistic feel.

With a faster feeling game and tons of cars on the road with the player, it seemed obvious that the car should take damage. As the race goes on, if the car is hit enough, it will start shedding pieces and begin bouncing. If the car is damaged enough, it will impact the car’s steering response. This added more realism into the arcade-style gameplay.

Implementing collision detection properly was a challenge for the team, since up to 39 CPU-controlled cars could be on the screen at once. Collisions could be minor taps, long grinds against another car, or car-flipping crashes. However, the team had gained a lot of knowledge handling the collision detection properly from their experience with Virtua Racing.

Rrrrroooooollliiiiiingggg Staaaarrrrrrttt!!!

Sega tapped Takenobu Mitsuyoshi for the soundtrack to Daytona USA. He had done the music for Virtua Racing and a few other Sega games in the early 90’s, but was unfamiliar with NASCAR racing. He decided to go in a different direction than Ridge Racer had, leaning away from the competition’s techno music and into full vocal rock and funk songs. The very first song a player would hear in the game is “Let’s Go Away,” which is arguably the most recognized song from any racing game. (Don’t agree? Come at me, bro.)

Misuyoshi recorded all of the vocals in the game himself9. He’s the “Rrrrroooooollliiiiiingggg Staaaarrrrrrttt!!!” guy.

With smooth gameplay, an advanced AI, and epic audio, what could possibly make Daytona USA an even better game?

The Power of a V8

Daytona USA was shaping up to be a great contender to Ridge Racer, but the team knew they could incorporate a key element to keep people coming back to the arcade game over and over again. And it was something that would completely wreck their competition.

Instead of creating a single player racing game like Ridge Racer, Daytona USA was envisioned to be multiplayer. And not just 2 players at once. Not just 4. But at its launch, Daytona USA took a nod from the Namco’s own Final Lap and their own Virtua Racing cabinets, and supported up to 8 cabinets linked together. Eight cabinets, 8 racers, all racing the same race against each other.

Not only would this allow friends to race against each other, but it would enable Daytona USA to take up a massive footprint in arcades across the world. Of course, arcades wouldn’t need to buy all 8 cabinets. Sega would sell single units or twin models for head-to-head racing.

The single-player cabinet would be known as the Deluxe cabinet, and featured an astonishing-for-the-time 50-inch projection screen, subwoofers under the seat and fully decked out cockpit. The game almost shipped with actual car seats, but those were removed before launch and replaced with easier to care for plastic seats.10

Daytona USA‘s Soft Launch

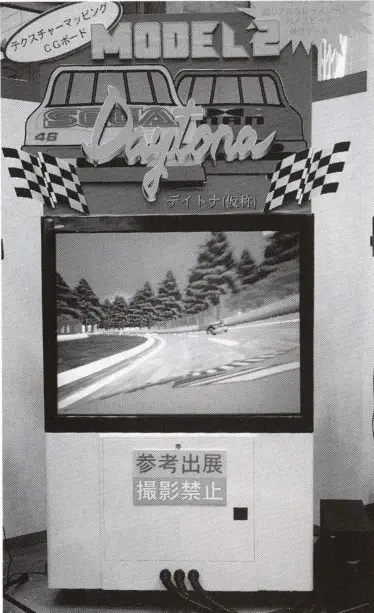

Daytona USA debuted a single prototype in Japan in August, 1993 at the Amusement Machine Show in Tokyo. The prototype was simply called Daytona, which some journalists started calling Daytona AM2 because of the team behind it. The prototype represented a game that was only about 5% complete, and the demo was unplayable.14

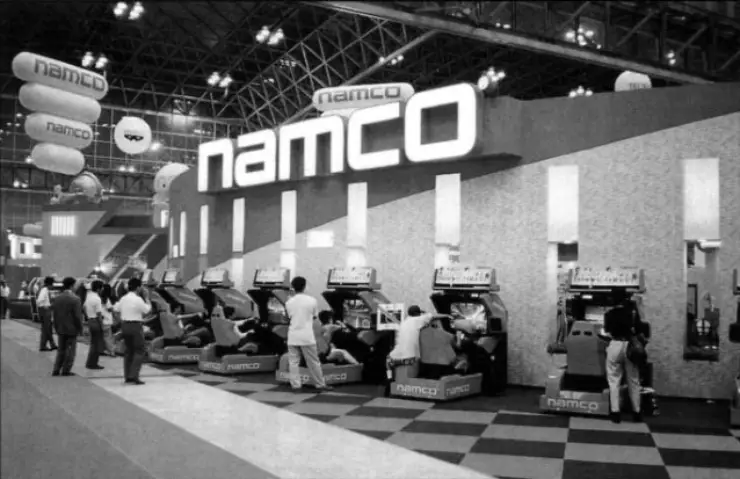

While Daytona USA looked okay, Ridge Racer got most of the attention at the show because NAMCO had their completed game cabinets front and center. And unlike Sega’s outing, people could actually play the game!

Gaming publications fawned over Ridge Racer, with only a select few noticing the non-playable prototype of Daytona USA.

Negative Press

In late 1993, Sega put a few Daytona USA cabinets in select arcades in Japan to get feedback testing but publications didn’t flock to them to try out Sega’s latest offering. Instead, journalists and gaming publications waited for Sega to display the game at gaming shows and expos. However, Sega kept rolling out their unplayable prototype at these conventions.

Gaming journalists started to take note. After seeing the same prototype at multiple shows, they started saying that Sega’s response to Namco’s flagship racer was “half-hearted.”14

The public was getting antsy to actually play Sega’s newest racer, but Sega of Japan delayed the launch of the game despite the AM2 team completing it in late 1993.

The rational for this delay was a potential shortage of components for the arcade units, which were made entirely in Japan. The new Model 2 boards were complex and Sega was still ramping up production when the game was ready for launch.

So, while Ridge Racer dominated the arcades, Sega sat back, waiting to make its move.

Global Release

Daytona USA made its global debut in March 1994, launching first in Japan and then later in North America at Chicago’s American Coin Machine Exposition. Finally, journalists and gaming publications could get their hands on the game that they had only been able to see videos of for months. The reaction was overwhelming. One conference goer in Chicago exclaimed, “My heart is still pounding after driving Sega’s Daytona USA. The graphics and overall game play are just stunning. It’s the game of the show.”11

Reviews for the new arcade racer were stellar:

“Creating new standards in technology, this terrific racer needs to be seen to be believed! It’s a must to play. It’s unbelievable.” Electronic Gaming Monthly

“This one-player deluxe racing simulator in real-time 3-D features “virtual reality” graphics the likes of which haven’t been seen before.” Play Meter

“As an arcade race experience this is unrivalled.” Games World The Magazine

Critics loved the game, but would gamers feel the same way?

The Final Lap

Despite a price tag near $20,00011, sales of Daytona USA cabinets sped off the starting line for Sega. Cabinet sales throughout 1994 helped push the game to compete head-to-head with Ridge Racer. Toward the end of 1994, Sega’s magnum opus of a racing game ultimately unseated Namco entirely. Daytona USA became the top grossing arcade game in the US in 1994 and 1995. The game became the top grossing arcade game in Japan in 1995.9

But what about Sega Europe and their concerns that making an arcade game focused on NASCAR wouldn’t bring success for them? Well, from August, 1994 to January 1995, Daytona USA topped the charts in Europe as the best selling dedicated arcade cabinet.13

Suzuki, Nagoshi and the AM2 team had a hit on their hands. Daytona USA more than delivered on its goal, leaving Ridge Racer in its dust and cementing the AM2 and Model 2 board as the industry leaders in arcade games.

The culmination of the vision of a US-based Sega president, the dedication of Nagoshi and the AM2 team to submerge themselves in a culture that was previously foreign to them, the composition of one of the best soundtracks in video game history by Mitsuyoshi, and the engineering of an unlikely ally in GE Aerospace gave birth to one of the greatest, if not THE greatest, arcade racer of all time.

Interesting tidbits

- You drive car #41 in Daytona USA because Toshihiro Nagoshi was told by a person that he loved that the number 41 would be his lucky number.6

- Driving in reverse on a track will still get laps treated legitimately, though you will always finish in last place.

- You can override the music for a race by holding down different “VR” buttons during the “Gentlemen Start Your Engines” Screen

- VR1 plays the song “The King of Speed”

- VR2 plays the song “Let’s Go Away”

- VR3 plays the song “Sky High”

- VR4 plays the song “Pounding Pavement” which is a secret song

- If you stop in front of the Jeffry statue and press “Start” repeatedly, he will begin to flip and spin

References

- Pole Position Wikipedia Page

- Final Lap Wikipedia Page

- NEXT Generation Issue #11 November 1995

- Kotaku

- Sega Model 2

- Daytona USA Dev Diary

- The Disappearance of Yu Suzuki: Part 1

- Retro Gamer, Issue #184

- Daytona USA Wikipedia Page

- Horwitz, 2018, The Sega Arcade Revolution: A History in 62 Games, McFarland

- Play Meter, Volume 20, Number 5, April 1994

- 1995 in video games, Wikipedia Page

- EDGE 001, August 1994

- EDGE 007, April 1994

One thought on “Daytona USA: Developing an Arcade Classic”