Dragon Warrior: The History of the Granddaddy of RPGs

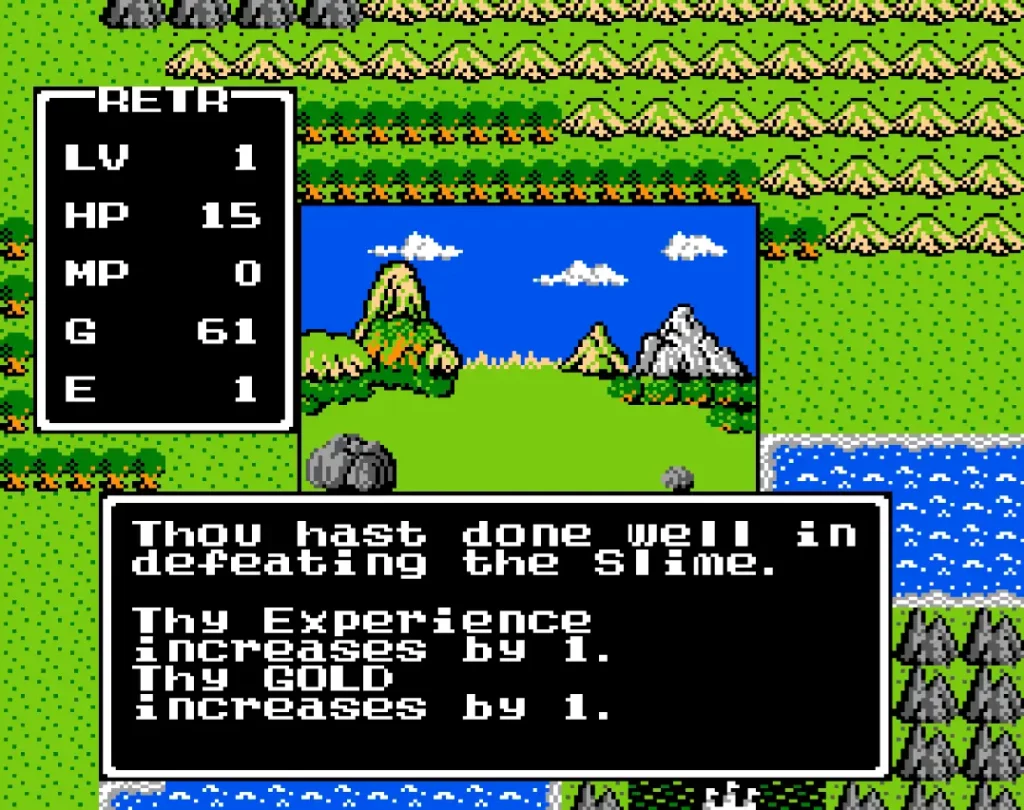

Sitting in the living room of my friend’s farmhouse, I held the NES controller while he went through Nintendo Power looking for the next magical item we could find in the game. We went through a desert and entered a town with overpowered enemies. After barely surviving a battle with an Axe Knight, we search the tile that Nintendo Power had pointed out. My I click “Search” from the menu, and low and behold, we’ve found Erdrick’s Armor. We both jump up and cheer. The best armor in Dragon Warrior is now ours.

Our story was not unique. Dragon Warrior (known originally as Dragon Quest in Japan) is one of the best selling franchises of all time. However, its development and rough launches were helped along by an unexpected ally. Here’s the story of how Dragon Warrior came to be and how it spawned one of gaming’s most successful companies.

Dragon Warrior/Dragon Quest Development

Before enthralling a generation of game players, Dragon Quest (Dragon Warrior in the US) began development in 1985 by the small Japanese software studio, Chunsoft. At the helm of the five person Chunsoft studio was a third year university student named Koichi Nakamura.

Koichi Nakamura

Nakamura learned how to create video games by diving into source code of other games and creating clones of games he liked. He was in only his first year of high school when he made a clone of Space Panic, the Donkey Kong-like arcade game. His version, which he called ALIEN Part II earned him 200,000 yen (around $1,000 USD) in royalties.1

Having caught the programming bug and now making a little bit of money from it, he went on to make a clone of Scramble, Konami’s side-scrolling shooter. Nakamura’s version netted him over 1,000,000 yen. By the end of high school, he had already accumulated over 2,000,000 yen in video game sales.

In 1982, Nakamura’s third year of high school, he entered an original game of his into a contest held by magazine publisher, Enix. His game, Door Door, was the runner up of the contest, netting him a 500,000 yen prize. The first prize went to a developer named Yuji Horii and his game, Love Match Tennis. Despite the second place finish, Enix published Door Door for the NEC PC-8801 and other home computers in 1983. It went on to sell over 200,000 copies for the NEC PC-8801 alone.2 By the time Nakamura went to university his software royalties were over 10,000,000 yen. It was time to get serious about this game development thing.

In his third year of university, Nakamura started the development company Chunsoft. One of the first releases for the company was a port of Door Door to the Nintendo Famicon (NES in the US) with Enix publishing the game. It was Enix’s first Famicon/NES game. The sales of game on the Famicon were more than double the sales of all other PC ports of the game.

After the success of Door Door, Chunsoft and Enix would team up to create another Famicon port called The Portopia Serial Murder Case. This time, Nakamura would collaborate with a game designer he’d run into in the past: Yuji Horii, the man who had bested Nakamura years before in the Enix contest.

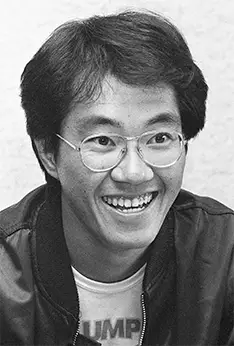

Yuji Horii

Yuji Horii never expected to beat the up-and-coming Nakamura in Enix’s game challenge. He wasn’t a developer by trade, but rather a writer for a manga magazine called Shonen Jump. But he had entered Love Match Tennis because he saw that his own editor loved computer games and Horii’s articles on computer gaming.5

After winning Enix’s contest with Love Match Tennis (which became Enix’s first video game), Yuji Horii created The Portopia Serial Murder Case, which released on the NEC PC-6001 in 1983. Horii liked the text adventure games that were being developed in the US, but noticed that not many were being created in Japan. The Portopia Serial Murder Case was an adventure game where the user typed commands to have “conversations” with the computer. The game had a main storyline, but also branched off into other subplots if users pursued different lines of conversation with the computer.

The game was a success on PC, but the text conversation aspect of it was frustrating to Horii. He wasn’t able to fit the language models he wanted to on the hardware available at the time. When Enix approached him about a port of Portopia to Famicon port, he knew that the text commands would have to go.

The Nakamura/Horii Collaboration

To bring Portopia to Famicon, Horii handed over the programming reins to Nakamura, who was only 19 at the time. There was apparently no bad blood between the two, and they got to work on the Famicon version. Hurii opted to change the interface for the Famicon, since text entry would be too cumbersome using just a controller, and made a command menu system similar to another adventure title that Horii had created a year before.

Along with the new controls, the two also added a dungeon-crawling section that was exclusive to the console version.

The game was targeted at mature audiences instead of younger audiences that the Famicon normally targeted. Despite this, it still sold over 700,000 copies and was a huge hit.

The two men worked well together on the title and while developing it, got an idea for another game. While Portopia had done well, Horii wanted to simplify the gameplay and make something for a wider audience. Something that Japan hadn’t seen much of…yet.

Getting Inspiration from the West

Horii and Nakamura both enjoyed the Western RPGs, Ultima and Wizardry, which allowed a player to walk around an environment and encounter monsters, buy goods, and build experience points to make your character stronger and stronger.

At the time, the US dominated the RPG genre. However, the games were intensive and for a lack of a better word, nerdy. Horii and Nakamura saw the potential in the genre, and set out to create something new and not only bring the RPG genre to Japan, but to the masses.

That game would be Dragon Warrior…er…Dragon Quest...

Bringing a Team Together

Horii and Nakamura had previously done games on their own, but Dragon Quest was bigger than anything either of them had ever done. There was a lot that they wanted to pack into one game.

Horii’s video game-loving editor at Shonen Jump arranged to have one of his magazine’s rising artists help out the Enix team on the new game. The artist was named Akira Toriyama, and he had just come off of the success of his manga called Dragon Ball.

Toriyama created the illustrations for the game, giving it an authentic manga style that would be easily recognizable. The monsters in the game became instantly iconic.

When it came to the music in the game, a classically trained composer by the name Koichi Sugiyama had approached Enix by sending in an Enix questionnaire postcard from a chess PC game. Sugiyama was a fan of video games and had composed scores for TV. When Enix received the postcard, a producer reached out to see if he was the same Koichi Sugiyama that had done TV scores. Upon hearing that it was, Enix asked if he wanted to create the score for an upcoming video game, which Sugiyama obviously agreed to.

Sugiyama later said that the original opening theme to the game took him only five minutes to compose. Due to his experience in TV, he knew that he only had a few seconds to catch the player’s ear, and paid particular attention to making the first 3-5 seconds of music as catchy as possible6.

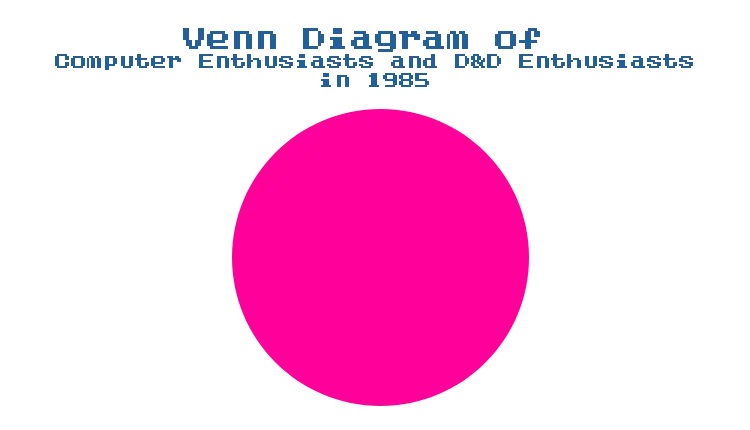

Taking and Removing D&D Inspiration

All RPG games, in the 1980s and even now, were compared and contrasted with Dungeons & Dragons. But for a game to be truly successful and accepted by the masses, Horii knew it shouldn’t require a background in playing D&D. Most RPG games at the time, like Ultima and Wizardry, were heavy in statistics and required a lot of advanced features and knowledge from the D&D universe. This was fine at the time, because the Venn diagram of computer enthusiasts and D&D enthusiasts in 1985 was basically a single circle.

But with the Famicon, it wasn’t nerdy computer geeks who were playing games. It was kids and their parents, from all backgrounds and some with little to no knowledge of computers. The masses didn’t play D&D, they played Super Mario Bros.

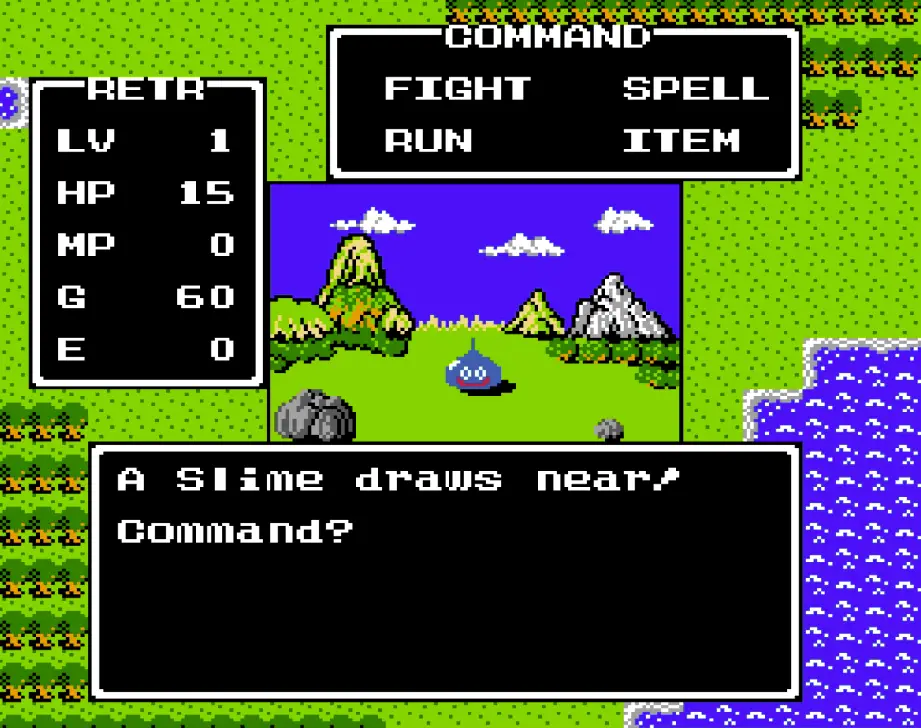

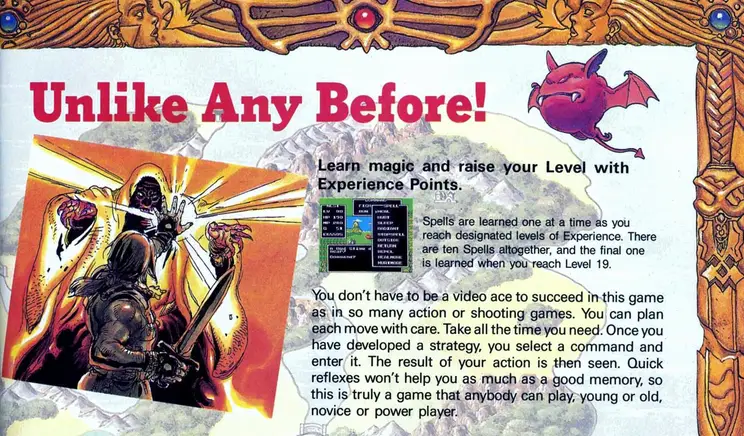

Dragon Quest needed to include the fun aspects of D&D, but cast away as much of the mundane as possible so it would have a wider appeal. Simple games like Super Mario Bros. were selling like crazy on the Famicon and Horii and Nakamura knew that to be successful, people should be able to pick up the game easily without reading a manual and be instantly engrossed in the story.

A key component of the game that came from D&D, other than battling monsters based on stats and random rolls, was having the hero progress and become more powerful over time. The XP component was absolutely necessary. But unlike it’s predecessors, it shouldn’t require hours and hours of monster encounters to level up at the beginning. The game would need to be crafted to allow the player to quickly see the results of their work at first, and then put in the work later to become powerful enough to defeat the final boss. The hero should also be able to easily add weaponry and armor through shops found throughout the game.

One component both Horii and Nakamura enjoyed in RPGs was being able to create and play as your own character. However, the Famicon didn’t have enough memory to create and store entire characters, so they opted to just have the player enter their name and they would then take on the role of the knight in the game.

Designing an RPG for the Masses

Horii designed the gameplay of Dragon Quest and the centerpiece of that gameplay was accessibility. Just simplifying the complexities of D&D wasn’t enough to make a great game. Other major changes needed to be made that set the game apart from others at the time.

Most successful games in the early 1980’s required the player to master moves and coordination to advance through the game. Jumps in Super Mario Bros. had to be timed right. Arcade shooters required quick reflexes. If a player died, they started over, losing any power-ups they had gained.

That type of design wouldn’t work for Dragon Quest. RPGs didn’t rely on quick reflexes and a player shouldn’t lose all of their progress if they died. Players would never forgive a game for that. The game was about exploration and building up their character while searching for the big boss to beat. The game wouldn’t be something to be completed in an hour. It’s story would take dozens or even hundreds of gameplay hours to beat.

Because of it’s scale, Horii designed the game to have a player’s death result in them being revived back at the starting castle, but the player would retain all of their spells, equipment, gold, and any extra things they picked up along the way.

However, death couldn’t come without consequences. Horii made the game take away half of the player’s gold when they died. Also, returning to the castle meant the player would have to retrace their steps to get back to where they perished.

Like the Western RPGs that inspired it, Dragon Quest would have an open-world map, where players could go around as they pleased without many physical barriers. To keep players from traversing too quickly through the map though, increasingly harder monsters were added as the player entered new areas. New players would quickly see that venturing too far from the starting castle would result in overpowered enemies quickly killing them. It was a barrier without being a physical barrier.

Another fun aspect of the game is that Horii showed the end goal of the game from the first moment a player sees the overworld screen. Near the castle the hero exits at the beginning of the game is the Dragonlord’s castle (Charlock Fortress), simply blocked by a river and mysterious black tiles. It was then up to the player to figure out how to get there. Adding this little bit of intrigue helped motivate players to grind through monsters and sections of the map to reach the ultimate goal.

In a nod to moving even further from his mature-rated Portopia, monsters were never “killed” in the game. Instead, they were “defeated”, which left the game some ambiguity.

Finally, the game itself would need to save the player’s progress. In the Japanese release, this was done through a password that the king would give you when you visited him to save the game, known as the Spell of Restoration. Entering the password when playing again would resume the player where they left off. This enabled the quest to last days, weeks, months or even years. It also allowed players to use an old password and try new strategies if another strategy didn’t get them the result they desired. However, when the game came to the US, this was not an option because another revolutionary system would be added to that version: saving the game to the cartridge.

Release and Reception

After a year of production, the original Dragon Quest (as it was known in Japan) was released in Japan in May of 1986. Despite the powerhouse team developing it, sales were initially low5, and threatened Enix’s early foray into video games. With the threat of losing a lot of money, a new marketing push was needed.

Luckily, someone on the team had access to a large publisher. That someone was Horii himself. Horii was still writing at Shonen Jump, which sold 4.5 million copies per week, and he began writing articles about RPGs and Dragon Quest to help boost sales. The gambit worked, and soon the game shot up in sales. Not only that, but people who gravitated to the game also bought more copies of Shonen Jump, increasing its circulation to over 6 million copies per week. The two mediums and companies once again worked together to each other’s benefit.

Dragon Quest sold over two million copies in Japan.

Because of his writing in Shonen Jump, fans of the series knew Horii by name, and he soon became one of the first video game designers to be known for his video game creation (Sid Meier would become the American equivalent after he added his name to Sid Meier’s Pirates! the next year). Not even the legendary Shigeru Miyamoto, designer of Super Mario Bros. and Zelda, was as well known at the time. Soon, Horii became the face of the franchise.

Beginning of a Franchise

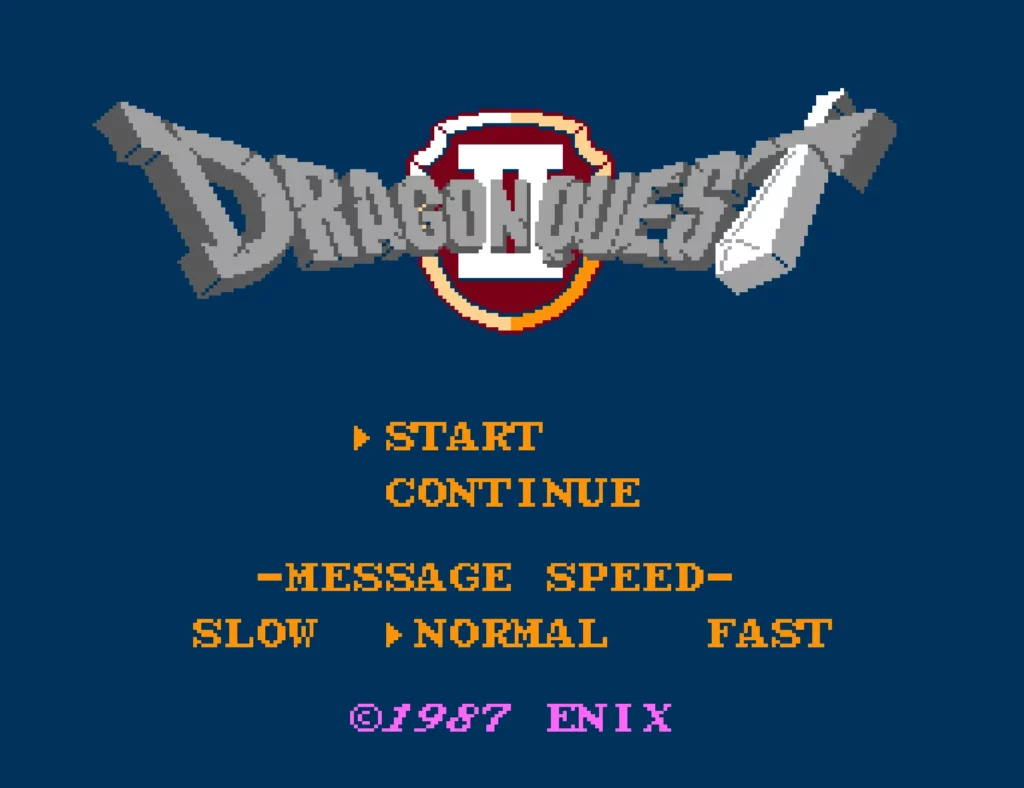

The massive sales of Dragon Quest in Japan necessitated a sequel. Luckily, the team all came back, again with Horii as the game’s designer and Nakamura as the game’s director. In fact, planning for the sequel began even before the first Dragon Quest hit store shelves. The goal was to make the game more exciting and change up the combat dynamic by adding more playable characters that were part of a party instead of having a single hero like the original. The sequel launched in Japan less than 10 months after the original and sold out immediately. In all, 2.4 million copies of Dragon Quest II would be sold in 1987.

Dragon Quest III came just a year after the sequel, and this time Japan was frothing at mouth for the third installment. The game released on a Wednesday, and resulted in so many children calling in “sick” to school that day that the Japanese Parliament would step in and decree that future Dragon Quest games would need to be released on only Sundays or national holidays.

The third installment of the franchise also brought some new technology to the fold. Instead of having to rely on long, cumbersome passwords, Dragon Quest III utilized a cartridge that could save the player’s file locally. This feature would also be utilized on another version of Dragon Quest, but instead of a fourth installment, Enix planned to bring Dragon Quest to the West.

Dragon Quest Comes to North America

Dragon Quest I through III were only released in Japan up until 1989. With their incredible success, Enix felt it was time to bring the series to North America.

The technology available to the team in 1989 was more advanced than what they had in 1985, so the graphics of the game got an overhaul, with the hero now able to turn in different directions while being controlled, and the overworld got a makeover to be more realistic.

Another feature that came to North America was the inclusion of a save ROM that Dragon Quest III implemented.

Adding more power behind it, Nintendo itself would publish Dragon Quest in North America.

But before the game could hit the shelves in North America, there was a problem. A very big problem.

Dragon Quest Becomes Dragon Warrior

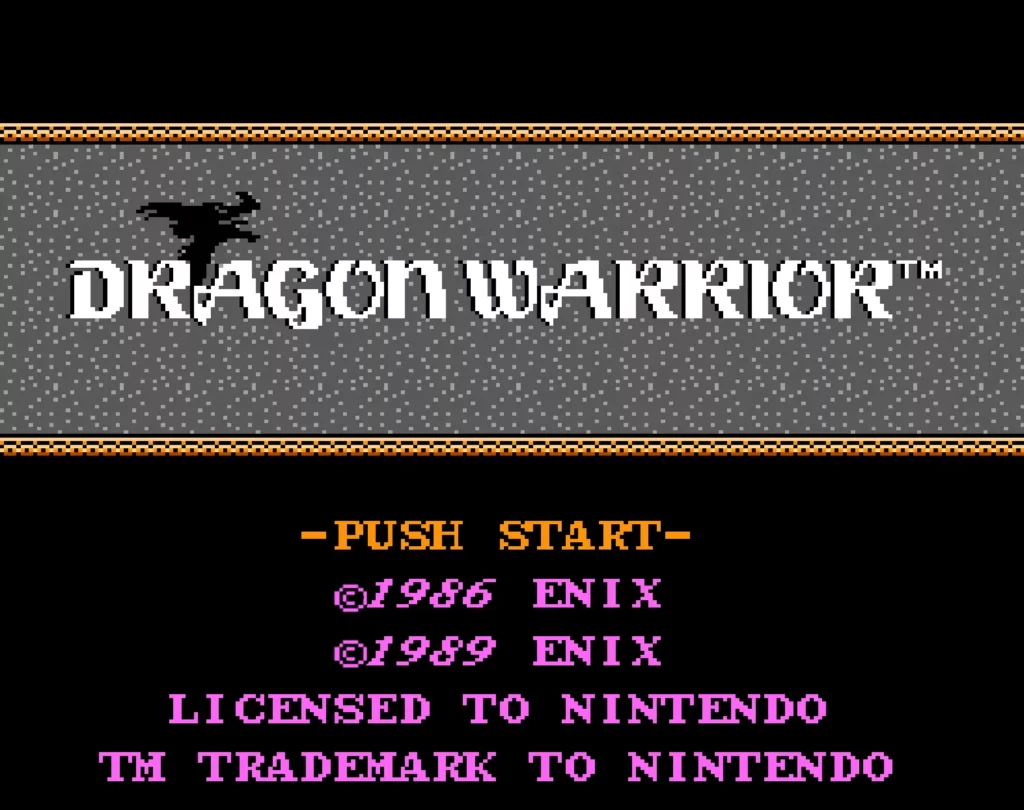

The name Dragon Quest was already used by a pen and paper RPG produced by Simulations Publications. That meant Nintendo couldn’t use the title that was a cult phenomenon in Japan for the North American release. Instead, they renamed the game to Dragon Warrior in North America.

The new-and-improved Dragon Warrior came to North America in August of 1989. Surely, the game would do well in a place that practically invented the RPG genre, right?

No. It was an instant failure.

Of all things, the North American release had been hamstringed by the success of Dragon Quest in Japan. Many other games had already utilized a lot of the mechanics that Dragon Quest pioneered, and brought those mechanics to the US before Dragon Warrior arrived. Also, a port of of Ultima III: Exodus had also come to the NES and was seen as a superior game by critics.

Despite appearing multiple times in Nintendo Power magazine to help promote the title, sales of the game were far below what Enix and Nintendo had predicted. Nintendo had expected the game to be a hit, much like it was in Japan, and produced cartridges ahead of time. Now, it was sitting on a stockpile of cartridges no one wanted to buy.

Magazine’s to the Rescue…Again

There is a legend that Atari buried millions of unsold E.T. cartridges in a dump in New Mexico because they couldn’t sell them. In 1990, Nintendo was facing a similar crisis with their big release of Dragon Warrior. Instead of destroying all of the extra cartridges and cutting their losses, Nintendo decided to simply give them away to Nintendo Power subscribers.6

At the time, a subscription to Nintendo Power only cost $20, while Dragon Warrior was retailing for $50. Nintendo’s giveaway worked. After sending out 7.5 million flyers to prospective buyers8, nearly 500,000 new Nintendo Power subscriptions followed (one of which was my friend), and re-subscribers also got the game. Once again, a print magazine came to the franchise’s rescue, first saving the Japanese launch and now saving the North American launch.

In all, over a million10 Dragon Warrior games were given away in the Nintendo Power promotion. An additional 500,000 games were bought at retail.

Dragon Quest’s Legacy

It’s hard to overstate the impact Dragon Quest had on the gaming world. The recipe it wrote for RPGs became the basis for many of the biggest RPGs that came later.

One such game came from competitor, Square. Square was struggling and nearing bankruptcy in 1987 when its game designer Hironobu Sakaguchi went all-in with a personal project to turn the company around. Drawing inspiration from Dragon Quest, he created a new RPG that released for the Famicon. Because he didn’t know if the game would be the last that Square would create, he aptly named the title Final Fantasy.11

The Dragon Quest Development Team’s Future

Koichi Nakamura would continue with Enix through Dragon Quest V, before deciding to stop making games for Enix. He and the rest of Chunsoft would go on to create and publish their own titles. Nakamura had to stop programming video games and focus on running the company. In 2012, Chunsoft would merge with Spike and form Spike Chunsoft.

In 1995, Horii and Toriyama teamed up with Final Fantasy creator, Sakaguchi, at Square to create the smash hit, Chrono Trigger for the Super Famicon/SNES. The RPG all-star team collaboration is considered to be one of the greatest RPG games ever made.

Horii enjoyed his celebrity status and continued to create Dragon Quest games, with character designer Akira Toriyama and music composer Koichi Sugiyama. All three have reprised their roles in most of the 30+ Dragon Quest games that have been created since the original. Unfortunately, Akira Toriyama passed away on March 1, 2024.

Square Enix

In 2003, the gaming world was rocked by the news that Enix would merge with competitor Square, to create Square Enix. The newly formed juggernaut had two of the most successful RPG franchises in Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy.

In 2002, Square Enix got the rights to the Dragon Quest name in North America, and all subsequent titles dropped the Dragon Warrior name in favor of the original Dragon Quest.

A Deserving Legend

Dragon Quest was a turning point for an entire genre that was once based in the West and only appealed to hardcore computer gamers. The game shifted the genre to the mainstream and also gave birth to the Japanese RPG with success that few franchises have ever seen.

The Dragon Quest series has sold over 85 million copies across the globe and is one of the best-selling video game franchises in Japan.12

And for me and my friend, we grinded through enemies over the course of that summer and nearing the beginning of the school year, we finally beat the Dragonlord and restored peace unto Alefgard.

Extra Fun Facts

The Portopia Serial Murder Case would later inspire Hideo Kojima, the creator of the Metal Gear games, to get into the video game industry.

The most important stat in the original Dragon Quest game is Agility. It ads to the defensive stats of the player and the player’s ability to run away from combat.

Dragon Quest speedrunners have figured out the timing and path to take to move from the starting castle all the way around the map to the first Metal Slime enemy. Killing the Metal Slime grants 115 XP and can quickly level up a player.

The world-record speedrun of Dragon Warrior is 23 minutes and 28 seconds. It requires manipulation of the random number generator to avoid enemies and get Excellent Moves while fighting.

Koichi Nakamura initially stopped making RPGs because his girlfriend at the time didn’t like them. He instead tried to make games that non-gamers would enjoy.

The first four characters of your name in Dragon Quest determines your starting stats and how your stats will increase as you level up.

Unlike Super Mario Bros., rescuing the princess in Dragon Quest is optional.

The Fighter’s Ring does nothing in the original NES and Famicon versions because of a bug in the game. In later remakes it gives the wearer +2 strength.

References:

- Koichi Nakamura Wikipedia Page

- Door Door Wikipedia Page

- The Portopia Serial Murder Case Wikipedia Page

- Nintendo Power Issue 221

- Power+Up, by Chris Kohler

- Dragon Quest Wikipedia Page

- Smart Bombs, Celebrating gaming’s most beloved flops – 1up

- The History of RPGs: How Dragon Quest Redefined a Genre – VG247

- How Did Nintendo Handle The Great Dragon Warrior Giveaway? – Press The Buttons

- Dragon Quest – Video Game Sales Wiki

- Sakaguchi discusses the development of Final Fantasy – MCV Develop

- Top 10 Greatest Japanese Video Game Franchises of All Time – Watchmojo

One thought on “Dragon Warrior: The History of the Granddaddy of RPGs”